Gold keeps hitting new records each passing week. Ongoing tensions between countries are shaping demand, causing the metal to react to headlines with frequent price moves. That naturally raises one big question: Is this rally setting up for a crash?

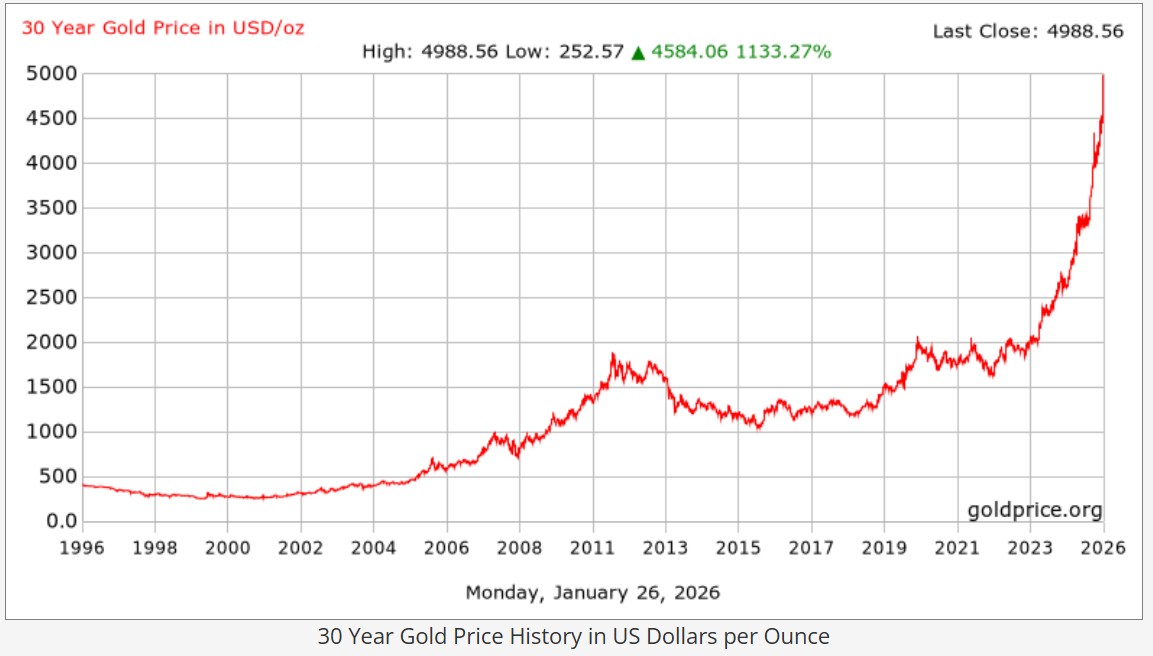

Gold climbed around 64% in 2025, while the S&P 500 gained about 16% in the same year. But the picture changes when you zoom out. A one-year chart looks healthy.

On a 30-year chart, the same move looks much more aggressive. The curve becomes steeper. The upside looks less normal.

For many people, this is the point where gold starts to feel vulnerable. The thought is simple: prices can’t keep climbing forever.

Now let’s look at the 50-year chart of gold and see what happened during the past major peaks, especially the ones that later turned into real downturns.

A gold crash is not the same as a normal pullback. Gold can drop 3%–8% in a week and remain in a strong uptrend. A crash describes a deeper, more structural decline, where prices fall sharply and stay weak for a longer period. In most cases, this happens when gold loses its “insurance” role.

As confidence slowly returns to cash and bonds, the dollar regains strength and real yields move back into positive territory. Gold doesn’t reverse simply because it climbed too far. It retreats when the environment shifts enough that holding currency starts to feel secure again.

The most famous gold crash started in 1980. Before that collapse, it had already spent a full decade rising. The 1970s were a messy period for the global economy. Inflation was surging. Oil prices shocked markets more than once. Geopolitical tensions were rising. Most importantly, confidence in the US dollar was falling fast. Gold benefited from all of it.

By January 1980, gold peaked near $850 per troy ounce. Then it dropped roughly 65%.

Here’s the part that often gets overlooked: gold didn’t fall in 1980 because it suddenly became “too expensive.” It fell because the conditions that pushed investors toward gold began to reverse. Gold functions as a trust asset. It climbs when confidence in paper money erodes, and it retreats when that confidence is restored.

So, what changed in 1980?

In the late 1970s, inflation was becoming embedded in people’s expectations as a lasting feature of the economy. Markets started to doubt whether the Federal Reserve would ever stop it. This credibility problem is what helped gold go parabolic into the end of the decade.

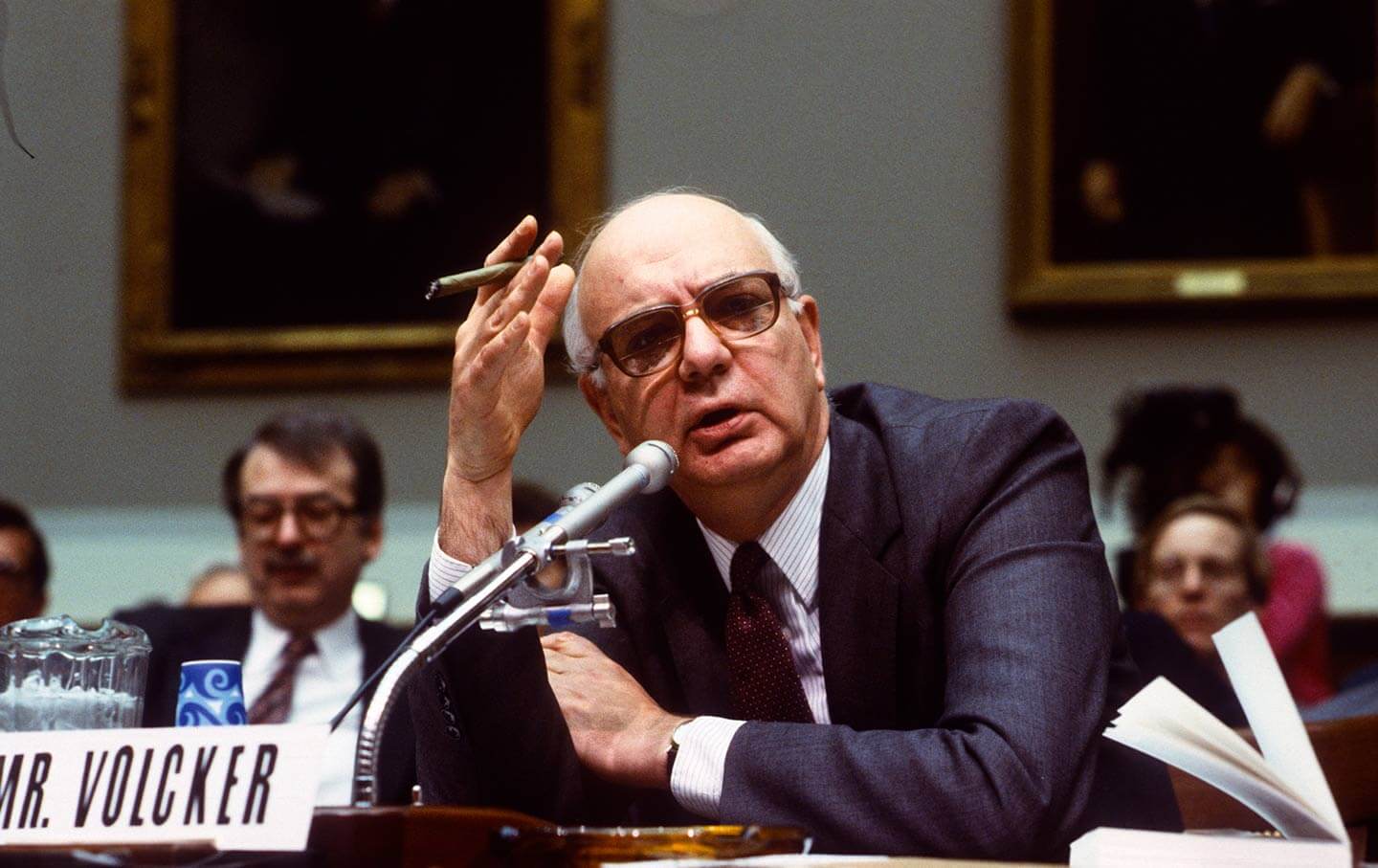

Then the Fed acted under Paul Volcker. Instead of slowly pushing rates higher, the Fed moved aggressively. Interest rates went to extreme levels, and at times, the Fed funds rate approached 20%.

That kind of policy is difficult to imagine today: mortgage rates climbed to around 18–19%, borrowing became punishingly expensive, economic activity slowed sharply, and a recession followed.

The Fed was willing to cause real economic pain to restore stability.

Another damage to gold came from real interest rates turning positive.

When interest rates rise above inflation, holding cash and short-term government bonds start to make sense again. Investors can earn a return that protects purchasing power. At that point, gold becomes less necessary as protection.

As rates pushed higher, two more things happened:

Once that credibility returned, gold no longer needed to play the role of “monetary insurance.” And that’s when prices collapsed.

The 1980 crash wasn’t a warning that gold always crashes after record highs. It was a reminder of what truly breaks a gold bull market:

After 1980, the next major peak traders often mention is 2011. Many people call it another “gold crash,” but it was not the same kind of move. There was no collapse. Instead, it was a long and slow decline.

Gold reached a peak of $1,920 per troy ounce in September 2011, and the context was clear. The world was still absorbing the shock of the global financial crisis, confidence in banks and the financial system was fragile, and central banks responded with ultra-low interest rates and massive asset-purchase programs, which became known as quantitative easing (QE).

That environment supported gold strongly because gold is often treated as protection against:

Many investors believed QE would eventually create runaway inflation. Gold prices reflected that fear.

The main reason gold peaked in 2011 is simple: the worst-case inflation scenario did not happen.

Inflation stayed under control for years. There were several reasons behind it:

As this became clear, investor psychology shifted. Gold started to lose the “urgent hedge” narrative that pushed it higher.

Around 2013, the Federal Reserve began signaling that emergency policies would not last forever. Markets started pricing in the end of QE and a future normalization cycle.

That triggered a chain reaction:

Gold was no longer the center of attention.

One important detail: gold did not break overnight in 2011. There was no single headline that “killed” the market.

Instead, gold entered a long period of weakness. It was a grinding decline that took years. By 2015, gold had fallen roughly 45% from its peak.

Just like 1980, the key lesson is not “gold hit a high, so it had to fall.”

Gold weakened because its insurance role became less necessary. Once investors felt the system was stabilizing, they were less willing to hold gold at premium prices.

So, 2011 teaches a different message than 1980:

Many people look at gold’s recent rally and instantly compare it to 1980 or 2011. It sounds logical at first. Gold hits a record. The market gets crowded. Then a crash follows.

The problem is, today’s environment is not built the same way. When you compare the real macro conditions, the historical parallels weaken fast.

Yes, interest rates are higher than the “zero era.” But that does not automatically mean gold should fall.

What matters for gold is not nominal rates. It’s the real return, meaning interest rates relative to inflation.

If inflation stays unpredictable while rates stay below it, purchasing power continues to erode. In that world, gold still makes sense as protection. This is the opposite of the Volcker era, where rates were pushed far above inflation and held there for years.

A Volcker-style rate shock is unrealistic today. In 1980, the US could tolerate extreme tightening. Debt levels were much lower.

Today, US debt is far heavier relative to the economy. That changes what policymakers can realistically do. If rates were pushed into double digits again, government interest expense would explode. That creates a hard limit.

So, if people say, “The Fed will just do what Volcker did,” the numbers do not really support that idea.

Another major difference is fiscal policy. The US still runs very large deficits. That matters because deficits weaken long-term confidence in the currency.

Even when inflation cools temporarily, the bigger picture stays fragile. Markets know governments often choose spending and stimulus over discipline.

Gold tends to perform well in that kind of backdrop.

This is one of the most important structural shifts. Central banks have been buying gold heavily. Many are trying to reduce dependence on the US dollar and diversify reserves. That creates steady baseline demand that was not as strong in past peaks.

This doesn’t mean gold cannot correct. It does mean the downside dynamics are different. There is more “natural support” beneath the market.

In the past, gold crashes often came with strong, sustained USD bull cycles.

Today, that is harder to assume as a long-term trend. De-dollarization is not happening overnight, but many countries are clearly trying to reduce exposure to the dollar system. That weakens the idea of a long, clean USD uptrend that would pressure gold for years.

Gold can always pull back, and that would not be unusual. If it is going to fall in a serious and lasting way, the macro environment would need to shift.

History shows that major gold downturns happen only when the market stops needing gold as protection.

So, what would need to happen?

Let’s be honest for a moment.

Look at what’s unfolding across the world right now: inflation pressures, widening fiscal deficits, rising cross-border tensions, trade frictions, shifts in central-bank policy, a softer dollar narrative, and more.

So, which of the conditions above truly looks realistic in the short term?

Silver Rally Ahead? Supply Deficit Meets Rising Demand

Silver Rally Ahead? Supply Deficit Meets Rising Demand

A new silver rally may be forming as supply deficits deepen and China’s demand grows. Here’s what is driving the momentum.

Detail Fed Rate Cuts 2026: How to Position Now

Fed Rate Cuts 2026: How to Position Now

Fed rate cuts in 2026 could reshape markets. See expectations, asset impact, and positioning strategies for bonds, gold, stocks, and USD.

Detail Analyzing the U.S. Labor Market Outlook for 2026

Analyzing the U.S. Labor Market Outlook for 2026

Year’s first jobs report looked reassuring. A closer breakdown, however, tells a more layered story about the direction of the labor market.

DetailThen Join Our Telegram Channel and Subscribe Our Trading Signals Newsletter for Free!

Join Us On Telegram!